I’ve been reading about off camera flashes for a while now, but can’t seem t figure out the whole logic behind the flash duration and it’s relationship with the shutterspeed.

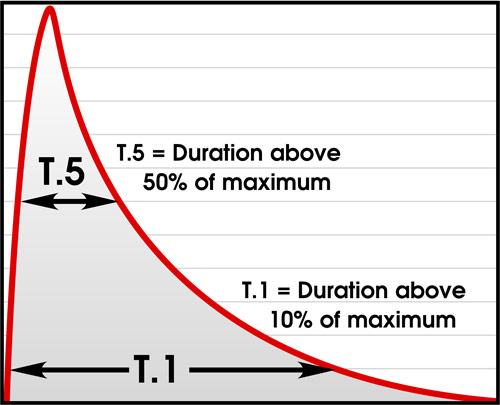

I understand that t0.5 (t0.1) means the amount of time it takes for the flash to lose 50% (90%) of it’s power, so if you want to freeze action it’s best to have as short t0.1 as possible (does it depends on the max power too?) ,

What exactly would be a good t0.5 and t0.1 and how do you connect it with shutterspeeds? I’ve also been looking into these flashes for a while now and connect the theory with the written specifications as well.

Anybody that could clarify?

__________

FluffyBunny2002: The flash duration and shutter speed are independent. However, many cameras use a double-curtain shutter, or electronic rolling shutter. The effect of these shutter systems is that at slow shutter speeds, the whole sensor is active, but at faster shutter speeds, only part of the shutter is active at any one time, and the activation travels over the sensor in a (relatively) slow fashion.

If you use a short duration flash, together with a short shutter speed on such a shutter system, then the flash will only illuminate part of the image. So, to get around this, cameras have a specified minimum flash sync shutter speed, which is the fastest shutter speed where the whole sensor is active. (1/75 for older mechanical cameras, faster these days). The electronics in the camera would trigger the flash at the point when the shutter is fully open.

Some cameras and flash systems, offer a special “fast sync” option, which allows the flash to illuminate the whole image at very fast shutter speeds – but what these actually do, is lengthen the flash duration so that the flash remains active for the whole shutter cycle (t0.5 = 1/50 or 1/75).

In general, the faster the t0.1, or t0.5 time the better the ability to freeze motion. The speed you need depends on what you are photographing, how much motion there is in the scene, how fast it is, how close you are cropped to the motion, and how much blurring is tolerable. As a rough guide, 1/500 will freeze most human movement, except for things like the the feet in a runner or dancer; 1/1000 will be often adequate for ball sports, but 1/2000 may be required in certain conditions (e.g. close cropped shots of tennis).

cville-z: It’s been a while since I worked as a profession photographer, but here’s what I remember from a couple years ago –

Most modern cameras have a traveling shutter system. In essence there are two “curtains” – at the start of the exposure the first one is closed, then it opens all the way, then the sensor/film is exposed, then the second curtain slides over to meet the first curtain, ending the exposure. Both slide back to their initial positions (remaining closed the whole time).

If you’re using a flash, you want to fire the flash at some point while the shutter is fully open, so the flash has to dump its light during the open part of the exposure.

This works pretty well up until faster shutter speeds, usually at 1/250th of a second (but higher or lower in some cameras). Beyond this point – the flash sync speed – the second curtain will start to close before the first curtain is completely open. At very high speeds what’s really happening is that a narrow moving slit exposes the sensor. This allows for fast effective shutter speeds – 1/2000 – but there’s no point at which the entire shutter is really open at once.

If you fire the flash at these higher speeds (say, 1/500th on a camera with a 1/250th sync speed) only part of the sensor will be exposed to the flash’s light. Fortunately, a “high speed sync” system allows the flash to be synchronized – I think through a system of lower power pulses – while the slit travels across the sensor.

If the strobe takes 1/500th of a second to discharge 90% of its power, though, an exposure of less than that won’t be able to get the full power of the flash.

If you’re using key flash (strobe provides the primary illumination), then you can treat the flash discharge time as if it is the shutter speed: set the camera for an exposure at the sync speed or below, dial back the ambient light to minimal, and fire away. If the flash takes 1/500th of a second to discharge 90% of its power, and you set it to full power, it’s equivalent to a 1/500th exposure.

-Malky-: Basically the flash duration is typically linked to its output. On most modern cobra flashes at 1/128th power you’re getting impulses of 1/25000 to 1/30000s.

‘hacked’ vintage Vivitar 283 can produce impulses in the 1/60000s range. That’s pretty close to what is achievable with a xenon discharge (~1/100 000s at the very most)

Beyond that you’d need an air gap flash and that’s dangerous to make or expensive and very rare to buy. Impulse here is in the microsecond range.

lindymad: You are in a train with no lights traveling at night time. The train is going past a wall that has 10ft breaks in it every 200ft.

If the train is going really slowly, you might take 10 seconds to pass a break. During those 10 seconds, you can shine a floodlight outside to see what is there, however you for some reason can only look straight ahead and you have no periphery vision, so you see one foot of what is behind the wall every second.

If, however, your floodlight is only on for 5 of those seconds, you won’t ever see the last 5 ft of what is behind the wall because you have no light.

Also, because you are going slowly, you might see a deer running along with the train. Over the 5 seconds that you have light, you can see how it runs.

Now imagine the train is going faster and those 10ft breaks whizz by and you only have 1 second to see what’s going on. The floodlight doesn’t need to be on for more than 1 second to allow you to see everything (but again, if it was only on for 1/2 second in this case, you’d only see the first 5ft). You see another deer, but much less of how it runs, because you only saw it moving for 1 second.

The train speeds up again, breaking all speed limits (and probably some laws of physics) and those 10 ft breaks go by in 1/125 of a second (IIRC that was the flash sync speed on my old Pentax Program-A). The floodlight is on and almost instantly off and yet another deer that was running along appears to be still because it has hardly moved in that time. Once more, had the floodlight lasted only 1/500 of a second, you would have only seen half of what was there, the rest being too dark.

(Note: This explanation applies to cameras with double-curtain shutters

ov3rdo5e: As previous comments mentioned the shutter speed of your camera and the flash duration is independent, but you have to sync the two together to get a correctly exposed image. As long you’re shooting in dark environment with the flashes as your only light source, the cameras shutter speed would not matter as long at it syncs – since not much light will be hitting the sensor from other sources than the flash. The sync speed would depend on the camera used, all should sync at 1/60. I have the BXRi/BRX500 heads and Elinchromes are great for freezing fast moving action to their extremely short flash duration.

PrionBacon: You sign up for a seminar to hear a famous speaker give a talk. The amount of time you are at the seminar is your exposure time.

When you enter the room, people are quite noisy overall throughout the seminar. The speaker is the flash. If the speaker has a long talk (long t) with not much intensity (low power) it’s hard to hear the speech over all the noise (hard to use flash in bright environments). If the speech is short and has high impact, you get the most out of it without needing to spend more of your time. This is easier if the room is quiet (dark environment).

However, you still need to be at the seminar to hear the speaker (shutter has to be open to collect light from the flash).

Blind artist, John Bramblitt, painted this for Dell Children’s Hospital

Source